It’s the starch that gets us – it’s simply sugar holding hands

In a nutshell

Starchy foods are rapidly converted to sugar. Our highly efficient digestive system breaks down bread, rice, pasta, and potatoes into glucose almost immediately, leading to unhealthy high blood sugar and insulin

The standard Western diet fits the definition of a fad diet. It promotes processed, high-carbohydrate foods, while restricting the natural fats and proteins humans evolved to thrive on, resulting in malnutrition

We are trapped in a state of constant carbohydrate surplus. Unlike our ancestors who consumed starches seasonally, modern food guidelines keep us in a perpetual cycle of excess sugar intake, making sustained weight loss and good health very difficult

The genesis of an idea

This post was prompted by a recent conversation I had with a friend about fad diets. We discussed things like vegan, carnivore, Mediterranean, and others. It left me wondering: what is a fad diet, anyway?

I consulted a few of the usual AI and search engine options and combined their answers as follows:

“A fad diet is a popular eating plan that promises health benefits but is often not supported by scientific evidence. These diets involve restrictive eating patterns and may not provide essential nutrients, making them unsuitable for long-term nourishment and good health”

The more I thought about this, the more I realised that the modern, industrially processed food recommendations in America and Britain meet the definition of a fad diet. They promote consumption of processed ingredients containing seed oils and large amounts of readily bioavailable carbohydrate, while restricting the natural proteins and fats to which we, as a species, are adapted and which we require for good health.

I’m of the opinion that our modern (fad) diet results in malnutrition and is driving the unprecedented rise in obesity, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, poor mental health, autoimmune diseases, and hospitalisations. We compound the damage by mischaracterising malnourishment as chronic disease, and by taking medications that fail to address the root cause.

I’ve written before about how over-eating carbohydrates leads to malnutrition. Try this article which introduces the dangers posed by starchy food. Now I’m going to explain how starchy food quickly ends up as sugar in our bloodstream because our human digestive system is so efficient. When we constantly eat a high-starch diet, we constantly have high levels of sugar in our blood. Persistently high blood sugar means persistently elevated insulin — and that makes us sick.

Bioavailable starch is confusing

Let’s start by reminding ourselves what we mean by bioavailable. I touched on this in Human Metabolism:

“Things in our food are considered bioavailable if we can absorb them from our intestine. In other words, they are biologically available to our bodies”

It’s important to recognise the difference between bioavailable carbohydrates — which we absorb — and those that pass through to feed our gut microbiota or exit as roughage.

To understand how overconsumption of starchy food makes us sick, and can even be addictive, let’s look at the efficiency of our human bodies.

The efficiency of the human digestive system

Let’s dispense with the complex textbook view of the digestive system (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Typical image (front and back) of the human digestive system

For this article, I’ve greatly simplified the system (Figure 2) to show the key parts and their purpose:

Figure 2: Simplified human digestive system showing major components and their role

I’ve divided it into: mouth, oesophagus (gullet), stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and rectum. For this discussion, the critical action on starch happens from the mouth through the small intestine [1,2].

Starch is digested as soon as we eat it

By digested, I mean broken down from a form we can’t absorb into smaller parts that we can absorb (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Our body starts to digest starchy food as soon as we eat it

This means that the high-starch food many of us eat all day long — bread, pasta, rice, potatoes, breakfast cereals, biscuits, pastries — doesn’t stay as starch for long. Our body immediately begins to digest it and convert it into a simple sugar (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Bread, pasta, rice, etc. doesn’t exist as starch for long before being absorbed as sugar

By the time our food reaches the end of the small intestine, all starches have been converted into small sugars and absorbed into the blood. Any sugary foods, fruit juice, or sodas are absorbed by this point too.

The way the human body efficiently converts starch to sugar

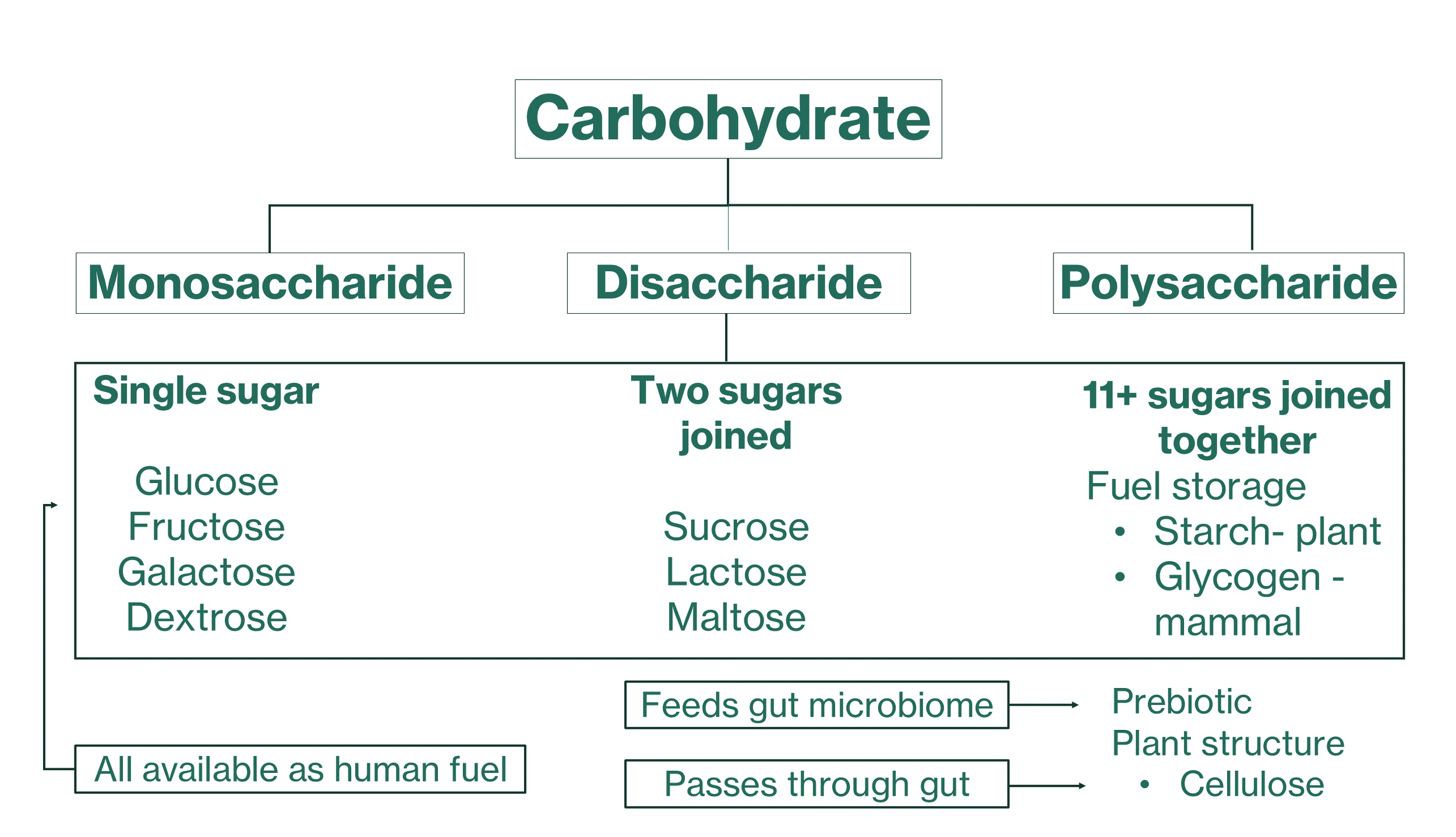

Here’s a quick terminology reminder (Figure 5):

Monosaccharide = single sugar (e.g. glucose)

Disaccharide = two sugars joined together (e.g. maltose)

Oligosaccharide = 3–10 sugars

Polysaccharide = many sugars (e.g., starch)

And when it ends in -ose, it’s a simple sugar — glucose (blood sugar), fructose (fruit sugar), lactose (milk sugar).

Figure 5: Starches and sugars that will be digested and absorbed as fuel or stored as fat

When we eat bread, pasta, pastries, biscuits (wheat flour), rice, potatoes, or sweetcorn, the starch (a polysaccharide) is made up of chains of glucose. Our body starts breaking this down in the mouth. Digestion takes place mostly and is completed in the small intestine, producing smaller sugars (maltose) and ultimately glucose — which enters the bloodstream (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The human starchy food digestion process.

Digestion process and sugar load

Now let’s remind ourselves of the sugar equivalence of modern starchy foods. I’ve used Dr Unwin’s data for Figure 7.

Figure 7: Sugar equivalent of recommended starchy food.

Dr Unwin compares common servings of starchy food to teaspoons of table sugar. A 150g serving of rice is equivalent to 10 teaspoons of sugar. A piece of toast equals about six teaspoons once digested.

Summary

It’s almost impossible to lose weight on our modern high-carb diet. Our bodies very efficiently and rapidly convert starchy food into blood sugar. This likely evolved to help early humans capture energy from seasonal foods like tubers, berries, and honey to build fat stores for winter.

Our modern diet provides these foods constantly — putting us in a perpetual state of autumnal carbohydrate surplus. People following the standard food guidelines are, in effect, always preparing for a winter that never comes.

Conversations with friends and family suggest that the risks of consuming too much sugar (whether from honey or soda) are increasingly understood. The same can’t be said for starchy foods. Because of our efficient digestive system, that piece of toast isn’t toast for very long — but sadly, our waistlines may be headed in the opposite direction.

References

Jeukendrup, A, and Gleeson, M (2024) Sport Nutrition (fourth edition). Human Kinetics

Kohlmeier, M (2015) Nutrient Metabolism: Structures, Functions, and Genes (second edition). NYC: Elsevier